Can net art, as we know it today, be taken seriously in the art world? I am working from the assumption that the definition of art is, “a form of human activity created primarily as an aesthetic expression, especially, but not limited to [my emphasis] drawing, painting, and sculpture” (Art Dictionary). There are many names, as well as definitions, for net art (i.e., net.art, web art, internet art, browser art, electronic art, digital art, cyberart and new media are names used to research this topic and to describe it today). In this paper I will show that net art appears to be following in the same footsteps as photography by non-acceptance as a serious art form in the world of high art. By establishing these facts concerning net art and photography;

- Both are mechanically produced

- Neither are considered to be in the same league with high art

- These artists followed their hearts and held their heads high

In my search to find references to validate net art as real art. I found there were very few sources that agreed with its function, purpose or its value as a true art form. Therefore, I concur with Rachel Greene’s findings, as she points out in her recently released book, Internet Art:

Though internet art has been discussed in a number of books and catalogues that have appeared since the mid–1990s, and a handful of net art archives are available online, the connections between net art and other art-historical movements are not well documented. In part, this may be due to the specialization of many net art critics and writers, whose methodologies are often grounded in internet culture and whose audiences remain mostly online (Greene 19).

History tends to repeat itself. Our culture advances because of change and with change comes conflict(s) or disagreement(s). It is through these conflicts/disagreements man is able to grow or gain knowledge. The conflict(s) with photography (just as with net art) emanate from a resistance to accept the artistic qualities that this genre of art has to offer. Case in point, Brook notes, “The claim that photography is or might become an art has been resisted for generations on the ground that photographs are essentially mechanical products, whereas artistic representations in forms of which painting is the paradigm engage the essentially free and imaginative human creator” (Brook 171). More evidence of this fact is supported again as Orvell reports, “Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) was not only the acknowledged great photographer of his day, [but he] work[ed] persistently to establish photography as a fine art on the level of painting” (Orvell 339). And even though Alfred Stieglitz was obviously highly regarded in his profession as a photographer, it still took many years before photography was even considered to be on the same level as fine art. An article from the Christian Science Monitor reinforces this point, “It took the better part of a century after the invention of the camera for photography to arrive at its own aesthetic instead of being judged by the standards of painting” (Grant 17).

During this period many photographers chose to take a stand, as Seamon asserts, “for more than half a century the issue of whether or not photography can be a medium for fine art has been, at least for serious photographers, more a distraction than a serious question” (Seamon 245). And for those photographers, taking this stand, the statement was probably more of a mental release allowing them to continue with their work unhampered. However, this position repeatedly shows up in other events, including a CRUSH conference where one of the photographers remarked, “It was a wonderful moment when it wasn’t necessary to be thinking of yourself as an artist to make photographs. Perhaps that’s an interesting comparison to today and net.art” (Ross D).

Upon further searching I found a curious comparison of history to poetry and photography to painting. And while I understand what Ross (agreeing with Sontag) is trying to say in the comparison of these relationships, I still believe they miss the mark:

To compare painting and photography in much the way that Aristotle compared poetry and history. Just as history seems subservient to the facts, so photography seems subservient to appearances. The photographer tells us how things look, just as the historian tells us how things happened. By contrast, the painter, like the poet, can improvise and generalize (Ross S 6).

I feel compelled to point out that Ross (Sontag) is not seeing photography as anything other than a means for reproducing the image of an object. Again, totally missing the mark, if one is viewing photography as an aesthetic art form. Ross quotes Sontag as stating, “The earliest controversies center[ed] on the question whether photography’s fidelity to appearances and dependence on a machine did not prevent it from being a fine art—as distinct from a merely practical art, a arm of science, and trade” (qtd. in Ross S 6). I fail to understand why Ross (Sontag) has chosen to focus on only one aspect of photography. The whole paper was focused on the point-and-shoot aspect of the camera. Either they chose not to see or they did not possess the ability to comprehend the many complexities that the camera as a medium can create in the hands of an artist. For when anyone lacks the ability to see the big picture, even worse, chooses not to see the big picture, you can be sure they never fully intended to look for it in the first place. Translation: if you don’t know what you’re looking for, then how are you going to see it?

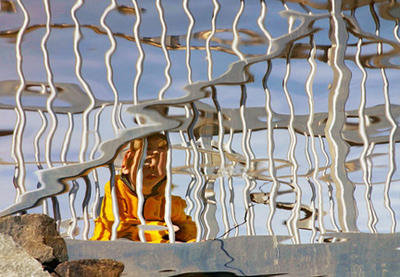

Here again, Ross and Sontag make a blanket statement that is totally incorrect, by saying a photograph is, “a frozen moment, and that their power comes from our knowledge of the causal process by which light rays deflected by objects create photographic images of them” (Ross S 10). Again they push their narrow-minded view of photography. It’s like saying all paintings must be impressionist or all etchings must come from woodcuts; neither of which is true. While I will agree that some photographs do present themselves as a frozen moment in time, I will respectfully submit that it was surely the intention of the photographer at the time. However, I totally disagree that all photographers set out with this single-minded intention for their photography. I have had the fortune to see some (and have taken some myself) very beautiful representational photographs that while I may or may not be able to discern the actual object in the photo it in no ways lessens the overall artistic impact of the image itself. (see photos below).

Duggan, Karin. Untitled. Summer 2004.

Ilachinski, Andrew. Noah and the Bridge. Summer 2004.

Based on what I have gleaned from the writings of Ross, Sontag, Scruton, and Walton, I wonder why someone who obviously has no or very little practical knowledge about a subject would present themselves as experts. From what I have been able to follow in their writings, they are making assumptions based on what they perceive and not by what they have personally experienced by using a camera. I am talking about hands-on, actually manipulating the camera to obtain the desired photographic result(s), or in the case of net art, sitting in front of the computer (keying) and pushing the software to its limits.

I have always felt the best part of being an artist is having that desire, that drive or that need (an itch) coupled with the ability (pardon the pun) to look outside the box. Of actually being able to create (scratch the itch) an aesthetic expression of a moment, emotion, or narrative through visual representation is what its all about. To push, twist, or manipulate the media, in this case with a camera or a computer, and being able to take it to the next level and beyond. This is what I am not reading in their papers.

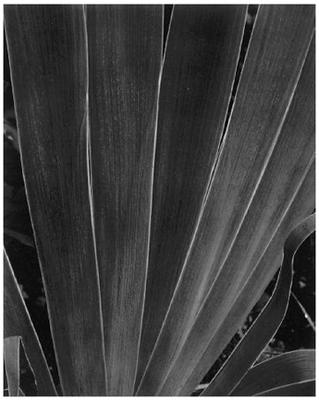

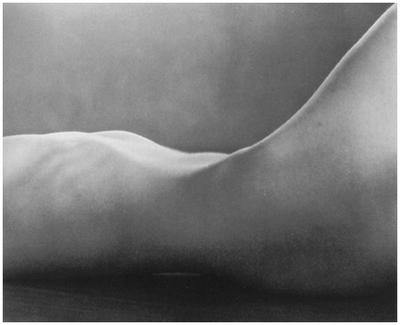

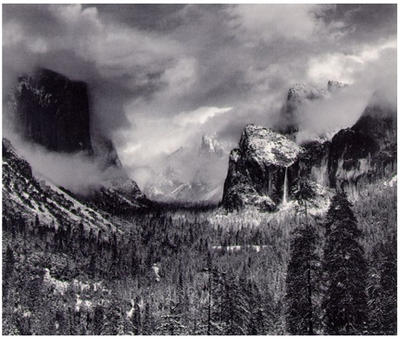

The artistry of photography has come a long way since the writing of these two papers by Sontag (1977) and Ross (1982). But where were they when Stieglitz, Strand, Weston, Adams and Kertész were producing this awe-inspiring photography from 1925 to 1937. (see photos below). In some of these photographs the image of the object is not easily recognizable, however, the visual impact of each photograph is truly breathe-taking. In any one of these photos the sheer depth of field, the myriad of tones, or the intimacy that each photographer is sharing, speaks volumes to the artistry of photography and the photographer.

Alfred Stieglitz. Equivalent. 1930. <http://www.masters-of-photography.com/>.

Strand, Paul. Leaves II. 1929. <http://www.masters-of-photography.com/>.

Weston, Edward. Nude. 1925. <http://www.masters-of-photography.com/>.

Adams, Ansel. Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park. 1937.

<http://www.masters-of-photography.com/>.

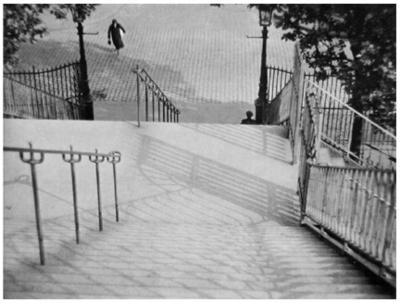

Kertész, André. Montmartre. 1927. <http://www.masters-of-photography.com/>.

Oddly enough it was Walter Benjamin who asked the right question, in his essay the Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, “How had photography’s invention changed the central idea of art itself? Or further, how had mechanization in the era of mechanical reproduction out of which flowed the invention of photography changed completely the ground rules of our social lives, the nature of representation, patterns of communication and corresponding aesthetic practices?” (Ross D). And now the computer (a mechanical devise) and net art (the art form in question) arrive on the scene and there is yet another invention that threatens to change completely the ground rules of our social lives, the nature of representation, patterns of communication and corresponding aesthetic practices. And this is a bad thing?

Everyone’s a critic and everyone has an opinion about what makes art. And there will always be those few select critics out there with their strong opinions who will not concede that photography (or net art) is a true art form. It seems to me that their narrow-mindedness is their greatest weakness and their greatest loss. I therefore have to agree with Paul Strand when he phrases it so succinctly and poetically:

Whether a water-color is inferior to an oil, or whether a drawing, an etching, or a photograph is not as important as either, is inconsequent. To have to despise something in order to respect something else is a thing of impotence. Let us rather accept joyously and with gratitude everything through which the spirit of man seeks to an even fuller and more intense self-realization (qtd. in Seamon 245).

Now in the case of net art, there have been many online forums debating net art and in this one rebuttal the focus seemed to shift and, “…all talk seemed to focus on critique of the interface, as if it were photography [my emphasis] or painting. A most disturbing example of a discussion of false distinctions was Charles Altieri’s pronouncement that “deep and moving” were adjectives that could not be used to describe net art” (Crush). Just to fuel the fire, Rachel Greene adds, “work that begins with or exists within internet or commercial formats can never rise above those limits to achieve the status of art” (Greene 13). And yet again, history repeats itself, as net art gets whacked, just as photography once did. Making net art the new unofficial redheaded stepchild of the art world.

At this point it would probably be safe to indicate, “There are probably many people working within this space who don’t necessarily consider themselves artists because they don’t want to limit themselves and their activity by a set of prejudices and predefinitions of artistic practice” (Ross D). Even now an accomplished and well-known net artist remembers his humble beginnings as he states for the record,

For example, here is a complex truth that I will never be able to explain in full: I knew exactly what I was doing when I began my online practice back in January 1993, but I had no real institutional support to help facilitate the discoveries that I was in the process of making and this, in fact, forced me to anticipate the future by questioning the validity of institutional structures while nomadically circulating within the ‘hypertextual consciousness’ of the world wide web itself (how is that for personification)?” (Amerika 72).

It does seem ashamed, as Bosma points out, that many “art historians and other theorists either tried to diminish the significance of art on the net and denied its uniqueness, or tried to put it in perspective within art history to get a better understanding of it; in either case, their position towards net.art was of course strongly influenced by their background” (Bosma). Even though they are consider professionals in their fields, they apparently have not caught up to the rapid moving pace of technology or the artistry of net art. And at sometime in the near future one is “hopefully, net art criticism will be more than the constant confusion and unpleasant feuds that arise every time attempts are made to openly discuss the features of art on the net. Accepting its existence would be step one” (Bosma).

But you can’t keep a good artist down, as Ameriak reports, “The last five years have seen networked digital artists come into their own. Not only have they been making challenging new work that blurs the intermedia boundaries, but also they have been inventing their own way of expressing and/or contextualizing this work for their distributed audiences” (Amerika 73). And just as photographers took a stand; we see net artists taking a stand, as White notes, “through their strategy of quotation and denial, net artists manage to elide their relationship to such high art “problems” as class privilege, hierarchical evaluation, claims of mastery, and the exclusion of other voices while still marking the importance and cultural worth of their work” (White 175). Many net artists also believe that, “… criticism is sometimes aimed at the works’ creators: that internet and software artists, often self-identified as programmers, are not ‘real’ artists” (Greene 13).

Sounds like the critics of the art world are implying, in order to be a serious (or to be taken as a serious) artist, one should never think of using a machine (like a computer or a camera) to create art. And if this is true, then why shouldn’t they (the art critics) make the same assumption in reference to the art of painting? To be taken as a serious painter, one should never think of using a palette knife or anything other than oils on the canvas. Then why stop there, lets really limit the artist’s ability to create by saying, “If you use anything other than a paint brush or apply anything other than oils to anything other than a canvas, then surely you can not consider yourself to be a serious painter.” Hopefully, the absurdity of these statements is obvious, whether one is talking about painting, photography or yes, even net art. Each artistic genre comes with its own tools (or medium, if you will) specific to its creation. What right does any one person or group have to pass judgment as to whether on not a specific medium or tool has validity in the creative process. Isn’t that what creativity is all about?

Simply put, art, however we describe it, is always evolving and with it evolves the medium(s) the artist uses in its creation. Each art genre has its own special place in our history and as mankind advances in history, so will the techniques of art. It makes no sense to resist net art as the next art genre, as Greene observes, “Though their tools and venues differ, internet art is underwritten by the motivations that have propelled nearly all artistic practices: ideology; technology; desire; the urge to experiment, communicate, critique or destroy, the elaboration of ideals or emotions; and memorializing observation or experience” (Greene 12).

In his speech, David Ross declares, “People who are thinking seriously about art, get it. It’s the lowest blow to say what you’re doing is not art. But that’s critics” (Ross D). In life there is good and there is bad. In the case of net art, it seems obvious the good outweighs the bad. The freedom to create using new technology as a medium is a big part of what net art brings to society today:

- Net art is an interactive intimate experience between the artist of his/her audience in real-time

- Net art is global

- Net art is created and viewed in the same environment and is not cost prohibited

- Net art is not class or gender specific and each viewer walks away with their own unique experience

If you get right down to it, history will repeat itself and it’s only a matter of time before net art (just as photography) becomes a recognized art genre.

Works Cited

Amerika, Mark. “Anticipating the Present: An Artist’s Intuition.” New Media & Society. 6.1 (2004): 71-76.

“Art.” Gallery Direct Art. March 15, 2004. <http://www.gallerydirectart.com/art-dictionary.html>

Bosma, Josephine. “Is it Spam? Noooo…Is It a Commercial? Noooo…It’s Net Art.” 1998. 24 Nov. 2004. <http://www.cityarts.com/paulc/SVA/vol2_no3_net_art.html>.

Brook, Donald. “Painting, Photography and Representation.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 42.2 (Winter 1983): 171-180.

“CRUSH: a response to CRASH: UC Berkeley Symposium on Critical and Historical Issues in Net Art.” 19 Feb. 2000. <http://www.conceputalart.org/features/crush/crush.htm>.

Grant, Daniel. “More Art Student Create on Digital Canvases.” Christian Science Monitor 94.157 (2002): 17.

Greene, Rachel. Internet Art. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2004.

“Masters of Photography.” Home page. 15 March 2005.<http://www.masters-of-photography.com/>.

Orvell, Miles. “The Inner Eye of Alfred Stieglitz; Literary Admirers of Alfred Stieglitz.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 42.3 (Spring 1984): 339-341.

Ross, David. “Art and the Age of the Digital.” Cadre Institute in conjunction with San Jose State University art gallery, New Mexico. 2 Mar. 1999. <http://switch.sjsu.edu/web/ross.html>.

Ross, Stephanie. “What Photographs Can’t Do.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 41.1 (Autumn 1982): 5-17.

Seamon, Roger. “From the World Is Beautiful to the Family of Man: The Plight of Photography as a Modern Art.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 55.3 (Summer 1997): 245-252.

White, Michele. “The Aesthetic of Failure: Net Art Gone Wrong.” Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 7.1 (2002): 173-194.

Suggested Net Art Websites:

<http://www.superbad.com/>

<http://www.markamerika.com/filmtext/>

<http://www.doctorhugo.org/dreamz/>

<http://www.art.net/studios/digital.html>

GMU

AVT 600 Research Methodologies

24 March 2005